I can’t remember the last time I was truly, blissfully bored. Not “I’m waiting in line so I check my phone” bored. Not “I have twenty minutes between classes and should be doing something productive” bored. I mean the kind of boredom that feels like a soft void — nothing pressing, nothing performing, just stillness. The kind that makes you lie on your floor, blink at the ceiling, and maybe, eventually, think of something kind of wonderful or weird.

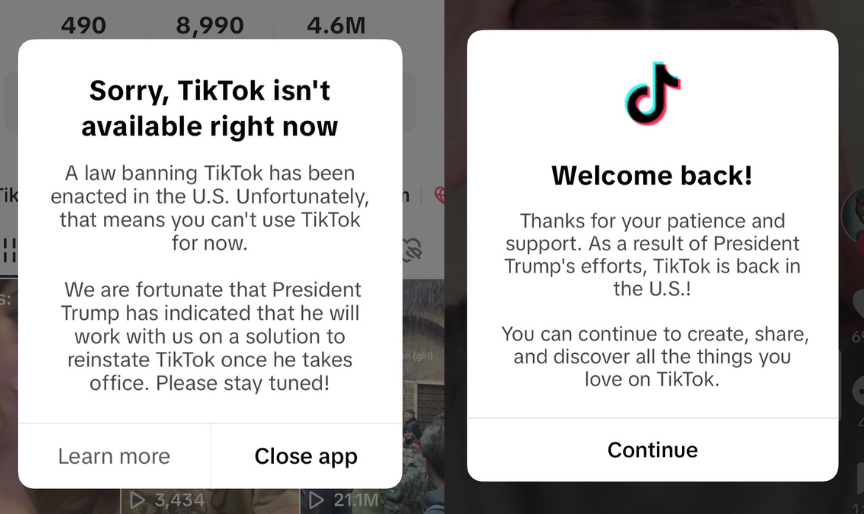

But boredom doesn’t just happen to us anymore. You have to go out of your way to be bored. It’s not like when we were kids and boredom chose you — when you’d sit in the backseat staring out the window with absolutely nothing to do and no one to talk to. These days, there’s always something to fill the space. Something to click on, respond to, check, scroll. There’s always a new tab open. Always a new southern mom on TikTok packing lunch for her seven kids with scary precision and a too-chipper voice. It’s not bad content — it’s just … inescapable.

And honestly? I don’t even really believe in boredom anymore. Not in the “ugh, I wish I had something to do” sense. There’s always something to do now. That kind of boredom — the classic, craving-for-stimulation kind — has been replaced by something else entirely. Something more complicated. People feel bored inside their routines. Like they’re stuck in a loop. Wake up, work, repeat. That’s not boredom, that’s stagnation. And it’s heavier. It’s a dull ache instead of a quiet space.

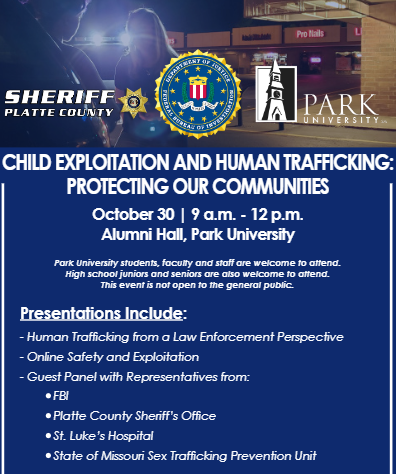

At a school like Park, a lot of us are running on tight schedules. We’re commuters, employees, caretakers, full-time students. I’m taking 18 credit hours, juggling multiple jobs, and maintaining a social life — even though it is kind of another job sometimes (a job I want to keep, for the record). We live in motion. But even when a quiet pocket opens up, I rarely let myself feel it. I reach for noise. I reach for distraction. I choose stimulation every time.

And maybe that’s the problem.

Boredom, real boredom — the kind we used to fall into — is where our minds actually stretch. It’s where we stumble into creativity or clarity or confrontation. Where we remember things that matter or ask questions we’ve been avoiding. We need that space. But now, to find it, we have to actively protect it. We have to choose it. And that’s hard.

German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer — often called the “artist’s philosopher” for the inspiration his ideas have sparked in creators — once wrote, “Boredom is just the reverse side of fascination: both depend on being outside rather than inside a situation, and one leads to the other.” He believed that boredom reveals something deeper about the human condition — that it isn’t about a lack of activity, but a lack of meaning. He even argued that boredom proves life’s inherent emptiness, because if life were full of true value, we’d feel fulfilled simply by existing.

I’m not sure I agree with him entirely (he was the philosopher of pessimism, after all), but I think he had a point. Boredom isn’t a flaw. It’s a signal. And in a world so saturated with content and convenience, the absence of boredom might be a red flag — a sign that we’re losing our ability to sit with ourselves and just … be.

So maybe I don’t miss being bored because I liked the feeling. I miss it because it meant something was still unclaimed in my day. Something open-ended. Something possible. And even if it felt uncomfortable at the time, I wish I could choose it more often — and I think a lot of us do.

Because sometimes, what we call boredom is actually just the space where our real thoughts live.